Introduction

By Rena

This October we invite you to join us in marking Black History Month (BHM); an annual celebration that champions and commemorates the contribution of African and Caribbean communities to culture and society. It is an opportunity to learn about and celebrate history but also to look towards a more equitable future. BHM is marked in February in the US and October in the UK. The idea came from African-American scholar Carter G Woodson. BHM has been recognised in the USA for nearly 100 years, while in the UK, it has only been formally celebrated since October 1987, on the 150th anniversary of Caribbean emancipation. Ghanaian analyst and council employee Akyaaba Addai-Sebo was the event organiser and it quickly spread beyond London to the whole of the UK.

The theme for BHM 2022 is Time for Change: Action, Not Words. Focus is placed on the double-burden Black people carry: experiencing racism and discrimination, and then being expected to fix the problem themselves. The theme aims to drill down into this with the hope of everybody coming together to make change for the better. It focuses on bringing the Black community together with allies and encouraging those allies to use their actions, not just their words, to support the cause.

Here’s some ways in which we can support BHM:

Recognise Black leaders in your local area

Champion diversity and tackle discrimination in your workplace

Raise money for/donate to charities, e.g. Stop Hate UK, UK Black Pride, Black Lives Matter UK, Black Minds Matter

Support Black-owned businesses

Hold a BHM event

The EmbRACE team recognise the need for continued action to tackle racism, and aim to celebrate Black history all year round whilst reflecting on its impact on the present day, which we hope is demonstrated throughout our newsletter pieces.

We kick off this edition offering an outdoors and running lens to anti-racism by two of our authors, and then look at the Black history of Notting Hill Carnival. We review an open letter that suggests ways organisations can address racism. Lastly, we offer a review of the play ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’; a suggested watch in our last edition, followed by some other events you may enjoy.

Something to Do

By Naomi

Trail Running

What’s the context?

Your feet pound across the ground, eating up expanses of gravel, moorland, open fields, crossing streams, splashing through mud. Your lungs and bones burn with exertion and your mind is entirely focused on the present moment. For some of us this may sound like the ideal way to spend a day, for others an absolute nightmare! For a lot of people trail running is a chance to escape the mundane, urban environments we live in. However, the outdoors isn’t the egalitarian playground accessible to everyone that it is sometimes depicted as.

For a long time the concept of “Running while Black” has been well known in affected communities. This came to the fore in 2020 after the death of Ahmaud Arbery; a young black man out for a jog, who was murdered in a racist attack. Affected people often have to take precautions before running. Perhaps changing how they dress and present themselves, when and where they choose the run, how fast and with whom. Systemic racism also plays a role. After World War II, communities of colour that arrived in the UK were funnelled into urban environments where they endured the consequences of limited access to green spaces and healing natural environments. The intersections between access to the outdoors and environmental racism reveal themselves when we examine the history of how communities have developed geographically.

Trail running, whilst being beneficial for cardiorespiratory fitness and general health, is a highly regulating activity for mental health when we consider the neurosequential model. Mindful breathing, rhythmic movement, the sensory integration and grounding of being in the natural environment creates a sense of wellbeing. This contributes to regulation, the ability to relate positively with others and access higher brain functions such as reasoning.

Many people have been drawn to the trails through this powerful “runners high”. One such person is Sabrina Pace-Humphreys. In her book Black Sheep: A Story of Rural Racism, Identity and Hope she describes her experience of growing up as a mixed race child in a rural community. She relates powerful and upsetting personal stories using her lived experience and describes her journey into trail running as an adult. The book culminates in her taking on intense personal challenges through her running and recognising the need to make outdoor spaces accessible for people of all ethnicities.

Sabrina is a co-founder of Black Trail Runners; an organisation that looks to empower Black runners in trail environments and contribute to increasing diversity and accessibility in the trail-running scene. Building a community of runners and allies during the Covid pandemic has been a huge undertaking. Black Trail Runners now has a podcast - The Checkpoint, and a huge virtual and face-to-face, event in May 2023 - Black to the Trails. The team has also taken on challenges like Ramsay’s Round - a classic Scottish fell running route conceived by Black trail running pioneer Charlie Ramsay in 1978.

What does it mean to me?

I love the outdoors and have always found it to be a place where I can be at my most free and my most authentic self. As a child I was encouraged to spend time outside playing and taking part in sports. Our downtime as a family was spent hiking, biking and camping. There were plenty of people around me that could teach me the skills you need to feel confident in the outdoors. I felt welcomed and safe in that environment. Now, as a queer adult, I find I feel safer in the outdoors than I sometimes feel in busier environments. I can look around and see outdoor role models I relate to like Rach McBride and Lor Sabourin. Representation matters, you have to see it to be it.

Intersectionality of experience and access is important. I realised through experiences at school that the outdoors wasn’t a safe, accessible or welcoming place for some of my friends. Particularly for friends from a non-White background, who often didn’t have family or community with existing outdoors experience or skills to teach. For these friends, experiences in the outdoors were limited to what was available through school. As an adult I’ve also seen that a friend with chronic health problems has limited access due to medical needs, and some of my female friends feel unsafe running on their own - particularly in remote locations.

To see an organisation like Black Trail Runners is so exciting for me. I want the outdoors to be accessible for everyone, so we can all share the joy I have found in these environments. To have an organisation that also allows adults to learn the necessary skills, rather than just focusing on youth schemes, is invaluable. The outdoors has vast physical, mental and spiritual benefits. We should work to actively incorporate inclusivity and create a welcoming environment for everyone to be able to enjoy these wild places safely.

Maybe you feel inspired? Look for local running groups and your nearest Parkrun. Check out Melanin Basecamp and Ultra Black Running. Sabrina started her running journey with a couch to 5k, you don’t need to be fast or go far - it’s all about getting outside and having an adventure.

Suggested reflections

Do you feel safe in the outdoors? If you go out for a run what, if any, personal safety factors do you have to consider? How does your answer reflect your privilege?

As a child did you have opportunities to access the outdoors and have appropriate outdoor gear? Did someone teach you the necessary skills?

If you see an advert for outdoor gear, does it feature people that look like you? If you access outdoor spaces or running communities, do you meet people who look like you?

How easy is it for you to access a green space from your home? What do you notice about the proportion of people of colour in your community and ease of access to a well-maintained public green space?

Would you feel confident to turn up at a Parkrun or race event? Why? Why not?

Maybe you are a long-time runner, what reflections can you make about your personal experiences with running and how these relate to an anti-racist dialogue?

Something to listen to

By Cath

Who’s the creator?

Young Hearts, Run Free is hosted by John Cassidy and Steven Watt. They share their thoughts and chat, as they give their take on the world of running. In this episode they interview Sabrina Pace-Humphreys; mum, grandma, ultrarunner, co-founder of Black Trail Runners and author of the book Black Sheep. Fast forward the episode to 17:47 where they introduce Sabrina.

What’s the context?

Sabrina shares her story of the things she has contended with in life. Her journey into running, how she dealt with racial abuse, and her passion to make a change so that running is inclusive for all.

Before she got into running, Sabrina didn’t see herself represented in running communities. She believed it was only for White, fit males wearing lycra. Her GP suggested going for a run to help treat her acute post-natal depression. This was a transformational moment; it gave her time to think about something other than the idea of wanting to end her life. For Sabrina, these were the first steps leading her to run more and use running to manage her mental health.

Sabrina is an advocate of breaking down barriers that prevent anyone from using running to improve their health and wellbeing. Her lived experience is of being the only Black person in her community, targeted with racial abuse. To then take the step to join a running club was huge, but once she did it, she found a place where she felt welcome and developed a sense of belonging.

What does it mean to me?

As a nurse working in critical care, I enjoy running as a way to look after my health and wellbeing. I regularly run trails, roads, and races. I do Parkruns whenever I can. I’m encouraged to know that there are many Parkruns across Greater Manchester and I often enjoy bumping into colleagues whilst taking part.

However, I have noticed a huge racial disparity in all running communities I have encountered. There is a noticeable lack of people of colour. I wondered why this is. I thought about it more this year, when I took part in a tail race in the Lake District. There were 2,500 runners from across the UK, and further afield, yet I could count on one hand the number of people of colour there. Later, I took a holiday to France to support friends taking part in the international ultra marathon UTMB in Chamonix. Again, counting on one hand out of thousands the number of non-White runners. Why is this?

Sabrina’s interview in the podcast above gave answers to my questions. It gave me insight into the barriers people of colour face when accessing running, and it gave me ideas for changes. I came away inspired and committed to do small things in my power which will make a change:

Invite colleagues to join me running

Share my basic map reading skills

Lend my gear out

Give a lift in my car

At my next race, ask the organiser/director what they are doing to encourage more people of colour to join the event

Share Black Trail Runners social media

Promote Parkrun more at work

Take the time, grace, and passion to show running is for all

Small things which will hopefully inspire others to be an ally and get people to listen and make a change, promoting inclusivity for all.

Forgotten history

By Holly

Notting Hill Carnival

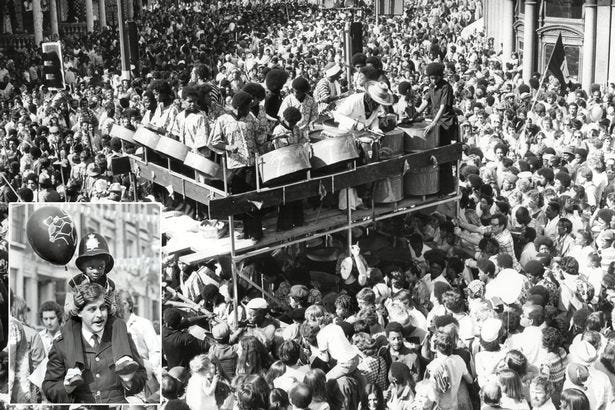

I have been taking part in Notting Hill Carnival in London since 2005, however I am ashamed to say I knew little of its history. I was first introduced to carnival in Trinidad and Tobago and immediately fell in love with the costumes, dancing, and euphoric atmosphere that the event delivers. I had learnt about the origins of the festival in the Caribbean islands and had naively assumed the London version was simply a tribute to the carnivals that are celebrated across the West Indies. Although there is a clear influence from the Caribbean, the origin of Notting Hill was in fact a response to the racial tensions and violence that were present in London. The development of the carnival is not linear however, and innumerable characters have played their part in the Notting Hill Carnival story.

To understand the beginnings of the carnival, we go back to the end of the Second World War. Migrants were encouraged to travel to Britain to fill the gaps in labour, a population now known as the Windrush generation. By the late 1950s Notting Hill and Brixton had the most concentrated populations of people from the Caribbean in the UK. Race tensions were high, and the fascist Oswald Mosley encouraged this with his slogan “Keep Britain White”, delivering propaganda that the new arrivals were taking peoples jobs and homes. Meanwhile, the new arrivals were facing colour bans in employment and housing.

Tensions escalated, and between August and September 1958 the Notting Hill Race Riots erupted, whereby mobs of between 300-400 White people undertook a week-long attack targeting the houses of Black residents. Poor race relations were escalated further with the racially motivated murder of Kelso Cochrane; an aspiring lawyer from Antigua, in Notting Hill in 1959. Many felt Cochrane’s murder investigation was complacent, and allegations of a police cover up began to circulate; the case remains unsolved. Activism was stepped up to government and the Home Secretary launched a public inquiry into race relations. These events were the catalyst by which activists and progressive organisations around the country began to make an effort to bridge cultural gaps and ease racial tensions.

One human rights activist, Claudia Jones, a Trinidadian and the editor of the first Black weekly newspaper in Britain, brought together seemingly disparate groups of immigrants to demonstrate, march, hold meetings and work with other anti-racist and anti-imperialist organisations. Crucially, Claudia employed the weapons of art and culture “in the face of the hate from the White racists”. She presented the idea of holding a Caribbean carnival to build unity and showcase Caribbean arts and culture. Her event was held on 30th January 1959 in St Pancras Town Hall, broadcast by the BBC. It was held indoors coinciding with Trinidad’s celebrations, as the English weather was too cold for an outdoor event. It was celebrated annually until 1964, when Claudia passed away. Claudia is widely credited with planting the seeds for carnival in the UK.

Next in the evolution was the week-long Notting Hill Fayre of 1966, developed by half-Native American Rhaune Laslett, in collaboration with the London Free School. The idea for the festival came to her in a vision, a dream - a “Hamblecha” as known by Native Americans - where she saw people of all races dancing together in the streets. The objective was to entertain children, lift the spirit of those living in poor slum conditions, ease the racial tensions still persisting in the wake of the race riots and to demonstrate the spirit of cooperation common to the progressives and activists living and operating there. Laslett said:

"We felt that although West Indians, Africans, Irish and many other nationalities all live in a very congested area, there is very little communication between us. If we can infect them with a desire to participate, then this can only have good results" (Grove Magazine, 23 June 1966).

Rhaune invited well-known steel pan player Russell Henderson and his band to help realise her vision. Their attendance changed the course of the festival. When they began playing pan, West Indians flooded the streets upon hearing the familiar musical sounds from home, whilst other locals were attracted by the new sound. In line with Trinidad Carnival, Henderson’s group led a procession through Notting Hill, gathering new revellers and participants along the way. They inadvertently put a Caribbean hallmark on the festival and word quickly spread to the other West Indian communities in England.

The week-long Notting Hill festival became an annual event growing each year. In successive years, although the carnival was still diverse and eclectic, it became progressively more West Indian, and specifically Trinidadian in flavour. The street celebration came to eclipse the spread of events and activities happening at a variety of indoor venues. As the festival developed, the Black Power movement was spreading from across the Atlantic and for some it became increasingly uncomfortable that a woman identifying as White was sitting at the helm of what was now seen as a distinctly Black Caribbean cultural affair. Rhaune Laslett’s authority, influence and control over the event gradually diminished and she retired due to ill health in 1970.

Henderson attempted to rescue the carnival by forming a committee to take the festival forward, however the idea floundered. By 1972 it appeared the carnival was off due to disorganisation and internal disagreements. With police harassment of Black men in the area, and continued raids on a popular West Indian restaurant which culminated in a court case known as the Mangrove Nine Trial, the community was on edge and rumours suggested the event was over.

When it became clear that no bands or groups were arranged to perform on the road, Merle Major, a young Trinidadian woman, stepped in to save the day. Merle hired a professional Trinidadian steel pan ensemble and the event went ahead. However, in 1973 Merle became pregnant and resigned as organiser.

In an attempt to save the event, Anthony Perry, director of the North Kensington Amenity Trust, decided to organise a public meeting. Only 5 people turned up, including Leslie Palmer, a local teacher from Trinidad. Palmer took over as the organiser broadening the event and made it more inclusive of all the Caribbean islands. He invited bands from different islands, and introduced static sound systems, live bands and live radio broadcasts.

Under Palmer’s direction, the carnival route was extended and generators were introduced. His organisational abilities laid a foundation for his successors at the helm of the rapidly growing carnival. In particular, Claire Holder, another Trinidadian and a barrister, was Notting Hill Carnival chief executive for 10 years. Despite being confronted with a multitude of challenges, Holder brought long-term stability to event’s leadership. One legacy of the Holder era was the formal division of Carnival into five disciplines: costumed masquerade, calypso, soca, the sound systems (mobile and static) and steel bands. Today, these comprise the ‘arenas’ of the carnival.

Today’s Notting Hill

The unique annual August Bank Holiday weekend event continues to showcase the colour, creativity, irrepressible energy, music, resourcefulness and rhythm of Caribbean and many other diaspora peoples. It is still proudly a community-led event, its ever-increasing popularity over the last 5 decades has seen it become a wonderfully diverse and vibrant event.

With over a million visitors expected each year, the carnival is considered the largest street event in Europe. Despite its success, bringing in around £93 million for London, the event is plagued with negative press. Each year it appears to be judged not on its festivities, wonderful costumes, local and international artists, DJs and steel bands, and the bringing together of cultures, but instead reports of its crime levels.

Events of similar sizes, including Reading, Leeds and Glastonbury festivals, rarely receive such scrutiny. Yet they also experience high levels of crime and arrests. This year stories filled the news of the devastating murder of Tayako Nembhard at the carnival. This tragic event reignited calls for the carnival to be shut down, or moved to a ticketed event in Hyde Park. In the 17 years I have been taking part, this rhetoric has been an annual threat. Each year there are rumours as to whether the event will go ahead. The bias in the amount of negative press coverage Nembhard’s death received was highlighted by the contrast in lack of reporting on the death of a 16 year old at Leeds festival over the same weekend. As Marvyn Harrison, author, broadcaster and founder of support group Dope Black Dads wrote on Twitter:

1.3m people attend Notting Hill carnival and 38 people get arrested. [0.0029%] “Nationwide headlines”

105k daily Reading and Leeds Festival and they have a 16 y/o dying from Ecstasy, 50 people were ejected for “serious disorder” [0.04%] and tents were set on fire. Silence…

Questions must be asked as to why there are continuous threats to the celebrations, and why the carnival receives the extent of unfair press. To save the carnival, Guardian journalist Maurice Mcleod made the wry suggestion:

“One possible solution: next year, instead of feathers and batty riders, we all wear wellies and gilets. Then let’s see the headlines.”

Something to read

By Martin

An Open Letter to Corporate America, Philanthropy, Academia, etc.: What Now?

What’s the context?

A letter written by an Equity & Leadership Consultant, following the death of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, to all major institutions. The open letter is aimed at Corporate America however I think this is a perfect letter for any institution including our NHS.

Who’s the creator?

Aiko Bethea is the founder of RARE Coaching & Consulting. She began her career as a grassroots community organiser working in underserved areas similar to the US neighbourhoods where she was raised. She studied law and became an attorney for the City of Atlanta overseeing federal, state, and local grants.

In 2009, Aiko joined the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, where she served for over seven years as Deputy Director overseeing a compliance team. During her tenure she created the first employee resource groups. She also led some of the first organisation-wide conversations about race, not as part of her job description, but as part of living the core values that she demonstrates in her life and work. Knowing that a critical amount of the foundation’s resources impact communities of colour, Aiko saw the importance of developing the conversation around issues of race within the organisation. In 2016, when Aiko was doing this work, there were rising public reports of police brutality in Black communities.

From 2017 to 2019 Aiko created and implemented the first organisation-wide diversity, equity & inclusion (DEI) strategy and developed the first diversity and inclusion department at Fred Hutch Cancer Research Center.

Currently, Aiko works as an Equity Advisor integrating DEI into the resources and curriculum of the Brené Brown Education and Research Group.

What does it mean to me?

I first came across Aiko Bethea from listening to an interview she did on the Brené Brown podcast Dare To Lead. I feel forever grateful for coming across her, this podcast episode, and the article which is talked about in the podcast.

There are many of us who want to do the “right thing” in equity and inclusion work but are scared and don’t know where to start. This article was written in just 30 minutes and gives concrete suggestions as to what to do in any organisation. It was the best thing I’d ever seen. I printed off copies and gave them to three managers in my workplace; a simple thing we could all do wherever we work.

Having read the article, I was struck by the way that data is used. Lumping together all people of colour when presenting data can hide important nuances. Following the publication of the UK Government’s 2021 Race Report, some media sources claimed that “all ethnic minority groups apart from Black Caribbeans perform better than White pupils at school”. However, this claim is unsupported by the granular data (see below).

In 2019, a higher than average percentage of children in state-funded schools from Chinese, Indian and Bangladeshi groups achieved strong passes in English and Maths GCSEs. But looking at these results from a ‘BAME’ perspective would have skewed the picture, masking the success of those particular groups and under-performance by others (Race Disparity Unit, 7 April 2022).

Figure 1 from Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities: The Report. Even this data doesn’t tell the story of how structural racism influences the experiences and parental/societal expectations of children in ethnic groups where a high percentage of students meet attainment goals.

The annual NHS Workforce Race Equality Standard reports are an important data set when considering racism within the NHS. It has consistently demonstrated that people of colour experience more harassment, bullying or abuse than White colleagues, not only from patients, but to an even greater extent from fellow staff members.

Despite these striking differences, low response rates to the survey amongst people of colour may actually disguise the true size of this problem. There may be many reasons why people of colour are less likely to complete the survey, for instance: they are more likely to be in frontline roles without dedicated access to a computer, and they may not believe that the organisation will act on the survey results.

In her article, Aiko talks about moving beyond the three Fs: food, fun and festivities. This made me look at equality, diversity, and inclusion communications through a different lens. I realised how a lot of organisations do not do much work apart from the three Fs. Whilst platforming and celebrating diverse cultures is valuable, it can lead organisations to engage only superficially with race-related issues. The practicalities of some such events can reinforce structural racism: people of colour may spend their own time and money to prepare food for their majority White colleagues in a bid to make their heritage “palatable”. This additional unpaid labour may go unrecognised.

When I first read the article, I felt the fire behind it and it gave me words to describe everything I had witnessed when organisations suddenly “woke up” during the summer of 2020, following the murder of George Floyd. Performative anti-racism was on the rise. I know some anti-racism social media accounts that suddenly jumped from tens of views a week to thousands of views. Cue full inboxes from anti-racism educators being asked questions that people wanted answering for free, which is a whole topic in itself!

I was inspired by Aiko’s words. She has written such a simple, yet powerful list. It would be easy for organisations, or any big institution, to follow her proposals. I will be taking it and reviewing it in all my future equality and diversity meetings.

Suggested reflections

How could you use this article to inspire your managers, your children’s schools, or relatives?

The article was written in 2020. How has your workplace advanced its anti-racism work since then? What role could you play?

Aiko’s Dare To Lead podcast episode explains the difference between diversity, equity and inclusion. How does anti-racism relate to diversity, equity and inclusion?

Something to watch

By Abs

To Kill A Mockingbird

What’s the context?

To Kill A Mockingbird is a novel published in the early 1960s and written by Harper Lee. The novel explores themes such as racial prejudice, family life and courage and bravery as well as the evolving nature of human morality. Winner of the Pulitzer prize, the book has been previously adapted for the big screen and now it has made its way to London’s West End. Currently playing at the Gielgud theatre, Aaron Sorkin’s adaptation has proven to be a big hit providing a snappy and powerful interpretation of Harper Lee’s work.

Who’s the creator?

Aaron Sorkin is an award-winning American playwright, screenwriter and film director. He has worked on films and shows such as The West Wing and The Social Network. Sorkin’s work is underpinned by common themes of duty and passion, wisdom and knowledge.

Harper Lee, born in April 1926 in Monroeville, Alabama was an American novelist famous for To Kill A Mockingbird and its much anticipated sequel, Go Set A Watchman, both of which have become stalwarts on most school literature set text lists. Harper Lee used both novels to explore the close minded, racist and prejudiced attitudes of a small 1930s town in Alabama. Much of the themes explored during both novels were largely based off Harper’s experiences growing up in Monroeville.

What does it mean to me?

Imagine getting a phone call on a dull Monday from your sister and her partner with the offer of theatre tickets to your favourite childhood book. This was luckily the case for me and I jumped at the offer. Having read and studied the book multiple times, it was an exciting prospect for me to see a theatre adaptation.

Growing up in the UK as a middle class British Sri Lankan male my experiences with overt racism have thankfully been few and far between. However, my lack of overt racial encounters may be due to a growing class divide that’s currently engulfing Britain. I very clearly used the word overt in my previous sentences to be clear that my experience with tacit racism and daily micro-aggressions have been plentiful and very negative. This West End adaption of a classic novel really lays out racial tensions and divides in a very raw manner that makes for uncomfortable yet very powerful viewing. The play served a stark reminder to me that whilst my tacit race related experiences haven’t always been the most pleasant, there is clear and overt racism happening all across the globe currently.

Whether or not this play is an adaptation of a 1930s novel, these prejudices haven’t been left in the past and are currently displayed through all parts of society across the western and eastern world. Atticus Finch was a flawed man but one who tried to help in his own way. Should we see him as a hero or simply someone doing the bare minimum that any good human should expect to do?

Another important theme set out by Lee and Sorkin is not to judge a book by its cover as experienced by the town Pariah, Boo Radley. Across my life, I feel that I have sometimes been detrimentally judged on how I might initially come across and my appearance, rather than people getting to know the real me.

Suggested reflections

If as person of colour, you were to ever be on the receiving end of racial abuse, do you think your White colleagues and friends would stand up for you? What factors might influence their behaviour?

Are you quick to judge people and then stick with that judgement or do you take time to form an opinion? How do racial stereotypes influence your first impressions?

Some things to attend

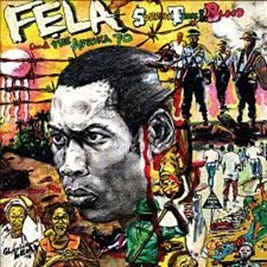

Fela Kuti’s Birthday: A Live Celebration

Fri 14 October 2022, 19:00 – 22:00

The Blues Kitchen Manchester

Fela Aníkúlápó Kuti was a Nigerian musician, political activist and Pan-Africanist. He created Afrobeat, an African music genre that combines West African music with American blues, funk and jazz. He has been referred to as one of Africa’s most "challenging and charismatic music performers" and was described “as a musical and socio-political voice of international significance”. Fela gifted the world songs like ‘Beasts of No Nation’, ‘Zombie’ and ‘Water No Get Enemy’.

On Friday 14th October 2022, Fela’s former bandmate Bukky Leo leads a group of the country’s most accomplished afrobeat musicians for his legendary ‘Felabration’, honouring the life and legacy of this musical icon. Hop down to Manchester’s heart of soul, blues and funk, The Blues Kitchen to join the part.

The Colour Purple

Tue 11 October - Sat 15 October 2022

The Lowry, Salford

Based on Alice Walker’s Pulitzer prize-winning novel and the Warner Bros/Amblin entertainment motion picture, The Colour Purple was adapted for the stage by Pulitzer Prize and Tony award-winners Marsha Norman, Allee Willis, Brenda Russell and Stephen Bray. Set in the deep American South, Colour Purple is the classic heart-wrenching tale of Celie, a young Black girl born into poverty and oppression who embarks upon a journey of discovering herself with the help of a few powerful and inspirational women in her life.

“With a profoundly evocative score drawing inspiration from jazz, ragtime, gospel and blues, this landmark musical celebrates life, love and the strength to stand up for who you are and what you believe in.”

Where better to watch this highly acclaimed production than The Lowry, Manchester’s iconic visual and performing arts venue.

Sheku Kanneh-Mason & Harry Baker

Sat 3 Dec 2022, 19:00

Band on the Wall, Northern Quarter, Manchester

Sheku Kanneh-Mason MBE is a British cellist, who initially shot to fame after winning BBC Young Musician 2016, becoming the first Black musician to take the title. He became a household name in 2018 after performing at the wedding of Prince Harry to Meghan Markle at Windsor Castle. Promoted by Through The Noise, Sheku performs a classical crossover with jazz pianist and close friend Harry Baker at Band on the Wall, Manchester’s famous eclectic live music venue.