How do we talk with our children about race?

Welcome to our first newsletter of 2022. In this issue we invite you to reflect on how you might discuss issues of race with your children, and to notice whether you observe, or are affected by, colourism. We also have a comedy series for you to watch, and Desmond Tutu’s Desert Island Discs to listen to. But first of all, we invite you to celebrate your colleagues and express your gratitude for their work by nominating them for a National Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) Health & Care Award.

As ever, we offer this content in the hope that it inspires you to take another step on your own anti-racism journey. If you’re on Instagram, we invite you to follow us there as well: @EmbRACE.Manchester

Something to do

Nominate a healthcare colleague for recognition

The National BAME Health & Care Awards 2022

Nominations are open until Monday 28th February 2022

Award categories and criteria available here

The National Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) Health & Care Awards celebrate BAME staff and networks across British health and social care. The Awards promote high standards of practice and advocate an ethos of BAME excellence in healthcare. Sixteen award categories cover everything from Emergency and Critical Care Healthcare Professional, to BAME Nurse of the Year. The awards ceremony will take place on 19 May 2022.

Something to read - Adults

I’m Chocolate, You’re Vanilla: Raising Healthy Black and Biracial Children in a Race-Conscious World - Marguerite A. Wright

What’s the context?

Dr Wright is a psychologist who counsels children and families on issues surrounding race. Every chapter she peels away layers surrounding why some Black children may have negative feelings about their skin colour. She talks about what age children start to notice and think about skin colour and race, and how to talk to children about this depending on their developmental stage.

Who’s the creator?

Dr Marguerite Wright is the senior clinical and research psychologist for the Center for the Vulnerable Child at the UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in Oakland, California.

What does it mean to me? (Noellie)

This helped me prepare for how and when to have these conversations at home, as well as be aware of negative influences they may come across in the community. Importantly this book is aimed at parents and teachers, so there is also useful advice on how parents can collaborate with their child’s school to address race issues in the classroom.

A word of warning though, this was written in 2000 and a lot has changed in the last few years in particular. Also, Marguerite Wright is a Black American, and race issues in the United States of America are seen through a slightly different lens to Britain.

Suggested reflections

How would you approach a conversation with your child about different skin colours? What would you like to do in order to prepare yourself for that conversation?

How do your own thoughts and feelings about race impact your children? What are you communicating to them, even if you aren’t openly discussing race?

Something to read - Children

The Colors of Us - Karen Katz

What’s the context?

Seven-year-old Lena is going to paint a picture of herself. She wants to use brown paint for her skin. But when she and her mother take a walk through the neighbourhood, Lena learns that brown comes in many different shades.

Through the eyes of a little girl who begins to see her familiar world in a new way, this book celebrates the differences and similarities that connect all people.

Who’s the creator?

Karen Katz has written and illustrated many books for children. Long inspired by folk art from around the world, she wrote her first book, Over the Moon, when she and her husband adopted their daughter from Guatemala, and she wanted to tell the story of welcoming Lena into their lives. Besides an author and illustrator, she has been a costume designer, quilt maker, fabric artist and graphic designer.

What does it mean to me? (Noellie)

Ideal for kids aged 2 to 10 (my kids’ ages!) but especially so for my six year old who is just starting to notice that some of his friends have different skin colours to him but isn’t sure how to talk about it. The book introduces talking about skin colour and difference in a positive and kid-friendly way. As my children have different skin tones they enjoy deciding whether they are like the kid with skin the colour of ‘cinnamon,’ ‘honey’ or ‘chocolate’ and take a lot of pride in how delicious they are.

Suggested reflections

How do your children think about race? Where do they get the language and ideas from in order to have a conversation about race?

Where do your children encounter fictional or historical role models from all racial backgrounds?

Something to watch

Black-ish - Disney+

What’s the context?

Black-ish is a critically acclaimed sitcom produced by ABC and can be found on Disney+ based on the lives of an upper class African-American family. They try to juggle their personal and socio-political issues of a Black family with wealth, whilst trying not to lose their identities. It tackles all sorts of topical issues, including the Trump administration and the murder of George Floyd, but with a sense of humour and heart.

Who’s the creator?

Kenya Barris is a celebrated American producer and director having made many television programmes which examine race as well as ageing and feminism (a lot with from the perspective of an Afro-American). These include ‘Could’ and ‘Coming 2 America’.

Mr Barris draws on his experiences growing up in a single-parent family in Inglewood, California to guide his projects ensuring they maintain a level of realism and truth to the Black community experience.

What does it mean to me? (Ben)

From the stand point of a White British man I’m obviously ignorant in a lot of ways. Whilst this series is not made to educate, it manages to teach without preaching. The insight it allows into the lives of a Black family and the various struggles they face is done in a funny, accessible manner. I have often felt intimidated at the thought of asking some of the questions that this series answers. Watching this series is like an easy way into the discussion. Be that as it may, there are some hard-hitting stories which not only give you pause but, at times, can make me feel quite uncomfortable. In particular, the questions about the different attitudes held by the ‘liberal left’ White folk of their neighbourhood. Another interesting feature of the series is how the older generations of the family, in particular the main character and father, Dre, try to navigate the ever-changing landscape of being Black in America along with being highly successful in his career. The disconnect between him and his children is something a lot of people will also identify with.

Suggested reflections

1. Are you comfortable laughing along with the show? If not, why do you think that may be?

2. How much humour do you think it is appropriate to use on the topic of race? Do you think there is a limit?

3. Has there been a point when you haven’t felt like you could laugh along with a joke that was made by someone of a different race? Particularly if it had race specific points in the joke? Why do you think you felt uncomfortable?

Something to listen to

What’s the context?

Eight tracks, a book and a luxury: what would you take to a desert island?

Desert Island Discs is a radio programme on BBC Radio 4. Each week a different well-known guest is featured, referred to as a ‘castaway’. The castaways are interviewed and invited to choose eight recordings (usually music), one book and a luxury item that they would take if they were to be cast away alone on a desert island. The programme plays their song choices whilst discussing their lives.

This episode features the castaway Desmond Tutu. It was released in 1994 and is 40 minutes long. It is presented by Sue Lawley, who was the programme’s first female presenter, and over the 18 years that she was on the show, she interviewed 750 people from all aspects of public life including politics, entertainment, science and sport.

There are over 2000 episodes by castaways from 1942 to today. You can listen to and download individual episodes or subscribe to the Desert Island Discs podcast.

Who’s the creator?

Desmond Tutu was the first Black Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town. Born in South Africa, he was known for his work as an anti-apartheid and human rights activist.

He started out as a teacher who enjoyed seeing children blossom. However, when the government at the time expected him to only train his Black pupils for a life of service, stating they should be taught just enough English and Afrikaans for them to understand instructions that would be given by White employers, he abandoned teaching and turned to the priesthood at age 25.

Desmond oversaw the introduction of female priests. After the activist Nelson Mandela was released from prison in 1990, the pair led negotiations to introduce a multi-racial democracy and end the South African Apartheid. Desmond later became the chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission under Mandela’s government. During this time, he investigated historical human rights abuses, campaigned for gay rights and spoke out on the treatment of Palestinians and his opposition of the Iraq war. He was praised for being an architect for South Africa’s multi-racial future, and his work was recognised in the award of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984.

In this programme, Desmond talks about his childhood and the realisation that Black children were treated very differently from their White counterparts. He recalls seeing Black children scavenging in the school bins, picking out clean food items that White kids, who received free school meals, had thrown away. The Black kids didn’t get the government’s free meals, and their parents couldn’t afford to provide them with lunch. This memory stayed with him forever.

The presenter, Sue, describes Desmond as a thorn in the side of the White South African government at the time. He was far from a passivist. He called out the deliberate racist policy that the White government at the time held, which was aimed at destroying Black people. He speaks about the death threats he received, some via his children. Yet he continued to use his position in the Anglican church to speak out against the injustices that oppressed his people.

What does it mean to me? (Rena)

I listened to this programme shortly after Desmond Tutu passed away, and hearing his smooth, calming voice dampened my sadness. His stories and snippets of his life were fascinating and very thought provoking. He uses beautiful metaphors to tell his story. When I listened to the programme the second time, whilst trying to collect my thoughts for this newsletter piece, I planned to skip the music to focus on his stories. But I failed; the music was just too mesmerising and gave me a sense of connection with this magnificent man, from classical to choir music in his home language. His favourite song choice was ‘We are the World’ by USA for Africa, on which he reflected that ‘despite all the differences, we are one’.

You can’t help but dwell on the difficulties and challenges that people of colour have faced for many years when listening to his stories. Hearing his first-hand account of a dark time, signified by the desperation of the children of Soweto, who were ready to give up their lives to oppose racism, is heart breaking. Over 600 South African Black school children died after revolting in a series of demonstrations and protests in 1976. These stories highlight how much damage has already been done when it comes to racism; experiences that will stay with people of colour throughout their lives. However, when I truly listened, Desmond’s positivity shone through, and felt contagious at times. I sensed that he always believed things would change for the better. And on reflection, when thinking about South Africa’s history, progress has definitely been made over the years.

Desmond Tutu planned many aspects of his funeral including the music. He chose the same Imilonji Kantu Choral Society to sing for him, 27 years after he featured them in his Desert Island must haves. His song choices provided the soundtrack to his inspirational life.

Suggested reflections

1. What eight songs, book and luxury item would you take to a desert island? How are these choices connected to your lived experiences - why that song or book?

2. How might the song, book and luxury item choices of those with power and privilege differ to those who don’t?

3. What comes to mind when you hear or read the term activist? Do you see someone like Desmond Tutu? Is becoming anti-racist perhaps a form of activism, requiring action to confront and call out racism?

Some words to ponder

Colourism

Colourism is a form of prejudice. It is the discrimination against, or maltreatment of, someone based on the shade of their skin colour. Typically, people who have a lighter complexion are perceived as better than darker skin tones.

“You must use the dark skin slaves vs. the light skin slaves, and the light skin slaves vs. the dark skin slaves. . . If used intensely for one year, the slaves themselves will remain perpetually distrustful of each other” – Making of A Slave, Willie Lynch (1712)

Colourism differs from racism as it can occur between individuals of the same race. However, the preference for lighter skin tones is rooted and founded in racism. Slave owners preferred lighter coloured slaves, deeming them more appealing to the eye and therefore better ‘house slaves’. As they served their masters more directly, ‘house slaves’ were of higher value and worth. In essence, lighter skin meant a greater proximity to power. They received better treatment than their darker skinned counterparts, which fuelled jealousy and distrust amongst the slaves themselves. In his speech, Willie Lynch describes deliberately using colourism to oppress slaves and corrupt cultural harmony by creating division. Even when emancipated, this colourist culture remained a thorn in the Black community.

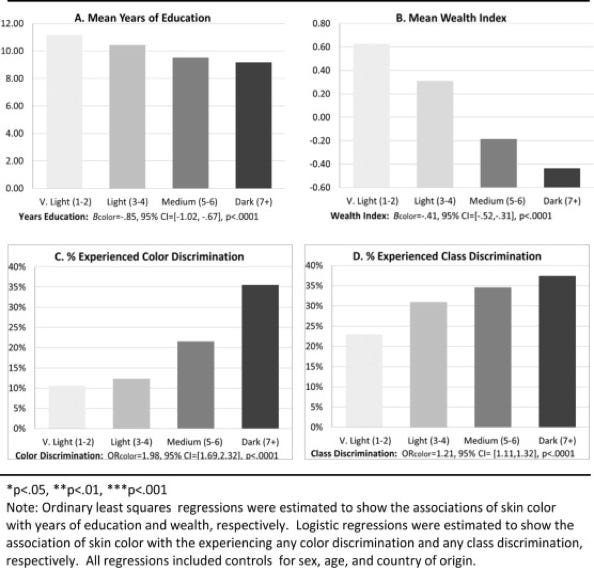

Colourism still exists today. As a result of the preference for lighter skin tones, victims of colourism make less social or economic progress within their communities. The charts below, from a 2014 study of almost 5,000 Latin American participants, show that darker skin tones are associated with less education and wealth, and more discrimination.

The continued existence of colourism is supported by research performed in Europe, Asia, Africa and the Caribbean. A study of arranged marriages in India revealed that mothers, offered a choice of two potential partners, would preferentially select a lighter-skinned partner for their child. The two options offered were photographs of the same person digitally manipulated to appear darker or lighter. In the Black-American culture, sororities, clubs and production companies were reportedly conducting the ‘brown paper bag test’ – a practice where those darker than a light brown paper bag were denied entry or certain opportunities. Colourism has led to widespread use of skin bleaching products in places like Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean. The global market for skin lightening products was 8.3 billion US dollars in 2018. People use harsh chemicals to lighten their skin tones and pass for being fairer skinned, as a way of avoiding the negativity and restrictions associated with being dark skinned or for some, just to feel more attractive.

Thankfully, with awareness groups, anti-colourism public figures and a general affinity for positive change, colourism is becoming less favourable. Those who experience its privileges are understanding its damaging nature for ethnic cultures as a whole and advocating for dark skinned people to be more visible in industries like fashion and media. Similarly, the idea that being closer to Whiteness equals power or excellence is slowly being debunked as other races become more visible in positions of power. Moving forward, it is important for everyday people to firstly recognise that colourism exists, understand the detrimental nature of it, and actively challenge it.

[The provenance of ‘The Making of a Slave’ text is disputed, and may not date back to 1712. It appears to have been first printed in a free publication called "The St. Louis Black Pages" in 1993. It was then posted on the internet by University of Missouri-St. Louis Thomas Jefferson Library Reference Department.]