Celebrating creativity

From the stage to the studio

Introduction

By Tom

This issue has a focus on creatives. Actors. Singers. Directors. Dancers. Artists. Authors. We will have opportunities to engage with, support, and celebrate the creativity of the people of colour featured in this edition. We will also see how structural racism affects those industries and the individuals within them.

In 1997 David Harewood became the first Black actor to play the role of Othello (a Black character) at the National Theatre in London. Up until that point, White actors, cast in the role of Othello, would use makeup to portray themselves as Black - a practice known as blackface. Michael Gambon was the last White British actor to wear blackface for the role of Othello in a 1990 production at the Stephen Joseph Theatre in Scarborough.

The same year that Harewood became the first Black actor to play Othello at the National Theatre, Patrick Stewart played Othello as a White man in a “race-reversed” production. Stewart stated that he had wanted to play the lead role, Othello, since his childhood, but “when the time came that I was old enough and experienced enough to do it, it was the same time that it no longer became acceptable for a white actor to put on blackface and pretend to be African”. Stewart’s answer was to reverse the races of the entire cast such that he, a White man, could play the role of a Black man. Whilst this created more roles for Black actors, as the majority of the cast would have typically been White as a result of casting practices at the time, it once again denied a Black actor the lead role.

Hopefully in the sections below we will all find something that captivates us and gives us an opportunity to explore, and celebrate, creativity.

Something to do

By Noellie

Visit the Marcus Rashford Mural

How do we talk to children about race? And how do we talk to children about racism? These topics can be scary, emotional and perhaps a little abstract for young minds to grasp.

My family watched England lose the Euro 2020 final to Italy, and then watched in horror as unforgivable racist abuse started towards three Black footballers, Marcus Rashford, Jadon Sancho and Bukayo Saka. How can we possibly explain that to our children?

In Marcus Rashford’s home town of Withington, Manchester, there is a mural by graffiti artist Akse, dedicated to the famous football star and campaigner for free school meals. The mural was vandalised after England lost the final, but then quickly covered up with hundreds of messages of support and also messages against racism.

Visiting the Marcus Rashford mural in Withington enabled my children to visualise what was being talked about in the media and in their classrooms. It was a catalyst to a conversation about a problem that otherwise we could pretend doesn’t exist.

What’s more, visiting the mural gave our whole family a sense of hope. Seeing with our own eyes the outpouring of support for Marcus Rashford and the way the community fought back, helped them understand how communities can pull together against racism and create anti-racist spaces.

Suggested reflections

Reflections I explored with my children at the mural included:

How do you think Marcus Rashford felt when he experienced racist abuse?

How can we make our own spaces anti-racist? For my children we talked about the school environment and their sports clubs.

Something to read

By Katherine

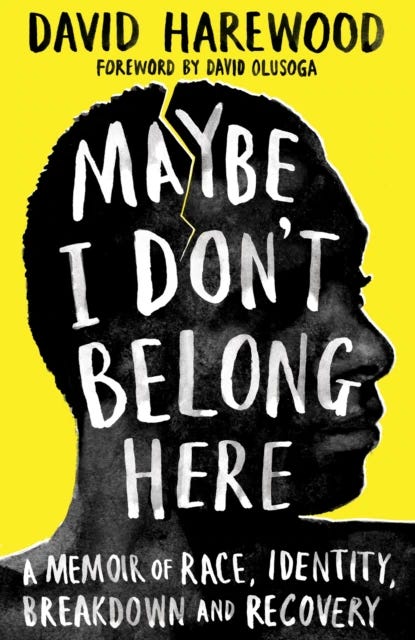

Maybe I Don't Belong Here: A Memoir of Race, Identity, Breakdown and Recovery - David Harewood

What’s the context?

“Maybe I don’t belong here” is a memoir written by David Harewood, a successful Black British actor. It details his career path and the challenges faced throughout his life. Harewood was born in Birmingham to Bajan parents, who had moved to England in the late 1950s/ early 1960s. A particular focus of the book is a psychotic breakdown Harewood suffered in his early 20s, not long after graduating from RADA. This event was precipitated by the conflict between his dual identities as both Black and British, the racism he faced, and the increasing pressure he experienced from existing in White spaces. Harewood recovered fully and went on to have a successful career, particularly in the USA.

Who’s the creator?

David Harewood MBE is a British TV, film and theatre actor. He is best known for his roles in US series such as Homeland and Supergirl. He also has a successful stage career, and in 1997, he was the first Black actor to play Othello (a Black character) at the National Theatre in London. After recounting his personal experiences in the documentary “Psychosis and me” (televised on the BBC in 2019), he took the decision to write his life story in the memoir “Maybe I don’t belong here”.

What does it mean to me? (Katherine)

This book is a moving account of the author’s lived experience demonstrating the devastating effect that racism can have on the mental health of Black people. On a personal level, I was shocked to find out, through the book, that Black men are four times more likely to be sectioned than White men, and Black women six times more likely to be sectioned than White women in the UK.

One point (that the author raises) that I found particularly thought provoking was that there is a fundamental difference between feeling British as someone born and raised here (as the author felt as a child) and being treated as British by those around you. Although the author’s childhood is set against Britain in the 1970s – including overt racism and the National Front – it made me wonder how many people still have a definition of British as equating to Whiteness.

Family and friends are a strong theme throughout the book, with the author recounting his own father’s mental health struggles, which occurred during the author’s childhood. He also credits his mother and close friends with being key to his recovery.

On a different level, the book would potentially resonate and feel familiar with many people as a story of a working-class kid aiming for more, and as a powerful story of a mental health crisis and subsequent recovery. I found the chapters of the book where the author meets with young people hospitalised following a psychotic episode particularly touching, which highlighted, especially, the importance of speaking out (about mental health, racism, and the impact of racism on mental health).

Suggested reflections

As individuals, or at the organisational level, is there more we can do to support the mental well-being of our colleagues who are people of colour? Can we (especially White colleagues) reduce the stress colleagues of colour might feel in having to navigate spaces in which they are under-represented?

The author is a professional actor, however, do you recognise instances where you or others might feel the need to act differently in uncomfortable situations when you or others are under-represented?

The author calls out the British Establishment’s claim to “not see colour” and therefore their failing to recognise a racialised society (which is a large part of the author’s decision to move his career to the United States). Do you recognise this claim from yourself or others, or organisations or mainstream media you’ve interacted with?

Consider supporting authors, and book sellers, of colour by getting your own copy of the book from a retailer such as Afrori Books. Every purchase is a vote.

Something to watch

By Siv

12 years a slave - (Netflix, Amazon Prime Video)

What’s the context?

Based on true events, this story is told through the eyes of Solomon Northup (played by Chiwetel Ejiofor) a free Black man, husband, father, and talented violinist from upstate New York who finds himself tricked, drugged, abducted, and sold into slavery in 1841.

Northup is chained and transported to the deep South, where he is renamed ‘’Platt” and stripped of his past life, his identity, and his humanity. He spends the next 12 years desperately trying to survive as he’s tossed between several different slave owners. The most malevolent of these is a cruel, sadistic slaver called Edwin Epps (played by Michael Fassbender).

At Epps’ plantation he crosses paths with Patsey (played by Lupita Nyong’o), another slave who is subjected by Epps and his jealous wife to unimaginable acts of physical and sexual dehumanisation. As well as enduring daily abuse and torture of his own, including a near death hanging experience, Northup is forced at gunpoint by Epps to partake in brutally whipping Patsey.

A chance encounter with a Canadian abolitionist secures his eventual freedom, however the deeply harrowing story of how survival can be a fate worse than death has already left its sombre mark.

Who’s the creator?

Sir Steve McQueen is a British Turner Prize Artist and filmmaker. He is best known for his movies, Hunger (2008), Shame (2011) and 12 Years a Slave (2013). The latter was based on the 1853 autobiography of the same name by Solomon Northup.

The film won the Oscar for Best Picture in March 2014, historically becoming the first Best Picture winner to have a Black director. Lupita Nyong’o won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for her harrowing depiction of tortured slave Patsey, becoming the first Black person from any African country to win an Oscar in any category.

In 2020, McQueen released Small Axe, a collection of five films set within London’s West Indian community from the late 1960s to the early ‘80s. Each one tells the hard-hitting story of a difficult and gruelling victory in the face of racism. The title references the African proverb "If you are the big tree, we are the small axe", which translates to collective small efforts against oppression having a bigger impact than you might think.

McQueen received an OBE in 2002, a CBE in 2011 and was knighted in the 2020 New Year’s Honours List for Services to Film.

What does it mean to me? (Siv)

This film plunges the viewer into an immediate, exhausting, never-ending nightmare of deprivation and dehumanisation. Slave-owner Epps’s repeated cycle of abuse and torture, followed by despair and self-loathing, leaves you resenting every part of his being as you realise that his self-loathing is born out of disgust at himself for sleeping with a Black slave. It reminded me of Ralph Fienne’s portrayal of the monstrous Amon Göth in Schindler’s List.

Silence is used cleverly and carefully throughout the film. The horrific hanging scene in which Northup is left hanging from a tree is deeply disturbing yet powerful. The imagery of the rest of the plantation ambling in silence around him as if he doesn’t exist, reminded me of the silence we continue to see in the face of oppression in current times. The story is made all the more harrowing because the characters who suffer the worst atrocities are robbed of any kind of closure. The final scene of reunion should be one of hope but instead I was left with a deep sense of grief and loss. Northup is alive, but his soul is crushed.

Throughout the film, there are tender moments of breath-taking beauty and hope. The Louisiana plantations have an inherent, calm and natural beauty. As you watch the light wind sweep through the cotton fields and the soft cotton floating gently into the clear blue sky it takes the viewer momentarily to a place of tranquillity and comfort.

Hans Zimmer’s moody musical score sews together the spectacular beauty and barbaric destruction of the film. I am reminded how during these dark times, music is both a tonic and a way of life. In that fleeting moment, it allows the oppressed to escape, feel safe and embody ‘somebodyness’. ‘Roll, Jordan Roll’ is a song of empowerment, community, solidarity and hope. I found myself feeling strangely guilty for enjoying these little moments of warmth and hope throughout the film.

This film is not for the fainthearted. However, I see it as essential education for anyone who wishes to understand and redress oppression. There are many subliminal messages throughout the film that prompt us to draw deeply uncomfortable comparisons with present-day life. It is a reminder that injustice and human rights violations didn’t end with slavery and continue to pollute society today.

Slavery is the biggest and bloodiest stain in human history. The first step is to confront and acknowledge its painful existence. This story is one that demanded to be told and heard. Ambitious, honest and horrific, once you’ve watched it, it stays with you forever.

Suggested reflections

How do the scenes of torture and dehumanisation make you feel?

What feelings do you have towards the different characters in the film?

What do you experience if you re-imagine the film with White slaves and Black slave-owners? Has this changed the way you feel in any way?

Do you think Selective Empathy plays a role in perpetuating injustice against certain groups more than others?

Something to listen to

By Matt

What’s the context?

In September 2021, British artist Little Simz (Simbiatu "Simbi" Abisola Abiola Ajikawo) released her fourth studio album - “Sometimes I Might Be Introvert”. It has been described as a “master class in modern songwriting with heaps of poise and a beating, soulful heart."

Who’s the creator?

Little Simz is an artist from North London who has dominated music lovers' playlists since 2015. Raised as the youngest child to Nigerian parents in Islington, London she was drawn to the stage early appearing in TV shows Spirit Warriors and Youngers. Her determination to release music independently meant that by the age of 21 she had released four mixtapes, five EPs and the studio album “A Curious Tale of Trials + Persons.” She has cut a unique path in the UK music scene creating experimental hip hop which undeniably represents the sound of London while breaking out of the box of Grime. Now aged 28 she has just finished touring for her fourth studio album “Sometimes I Might be Introvert”.

What does it mean to me? (Matt)

I wanted to share this album not necessarily because it’s an explicitly political or anti-racist album, but because the vulnerability, positivity and power of this album is something that I think the world needs as we all try to recalibrate post COVID. Simz’s vulnerability on this album shines through. Whether it’s the voice of self doubt in the little skits between tracks or tackling her complex relationship with her father on “I love you, I hate you.” Her openness creates an album that feels deeply personal and uniquely hers. In an NME interview she said about writing the album:

“I struggled with it because it is very personal, like having someone read your diary. But I think I understood that this is bigger than me and I know this has the potential to help someone. Above all, it’s me saying my truth and I think there’s great power in that. There’s great strength in vulnerability, so I persevered and I’m really happy I did.”

Even though Simz tackles difficult topics, the overwhelming vibe of this album is one of positivity and self-actualisation. “Woman” featuring Cleo Sol (Cleopatra Zvezdana Nikolic) is probably my favourite track and emphasises the importance of not just celebrating yourself but empowering those around you to celebrate themselves as well.

Simz’s music is so unique, probably because it is produced independently, without the help of a record label. The music industry has improved its racial diversity in recent years, particularly at entry-level positions where people of colour made up 34.6% in 2020. However, only 19.9% of senior executives in the UK music industry are people of colour. This is in stark contrast to the racial diversity of artists and probably goes someway to explaining the problematic actions of record labels and award shows in the past, such as marketing the genre “Urban” as a catch all description of the huge spectrum of Black music.

In 2020 after winning Best Rap Album at the Grammy awards Tyler the Creator said:

“On the one side, I’m very grateful that what I make can be acknowledged in a world like this, but also it sucks that whenever we—and I mean guys that look like me—do anything that’s genre-bending, they always put it in the rap or urban category.”

Simz lost out to Adele at the 2022 Brit awards for both Artist of the Year and Album of the Year, but claimed Best New Artist. Anyone watching her meteoric rise over the past five years would probably dispute that title. Nonetheless, Simz doesn’t care. She’s fiercely independent and that means the industry will always be playing catch up.

“At the core of it, I just want to continue to make art. I keep trying to push myself and better myself while having a great network or support. It’s a recipe for greatness and, with this album, I think I’ve unlocked something in my brain.”

Suggested reflections

What words, images, and ideas come to mind when you think of music created by contemporary Black artists?

What effect do you think vulnerability has on your friends, family or colleagues?

What are the consequences of the difference between the comparatively high number of people of colour who are content creators, and the comparatively low number of people of colour who are music industry executives?

Something to attend

Between Tiny Cities - Dance

10-12 May 2022

Contact Theatre, Manchester, M15 6JA

Full price £18, concessions available

In Between Tiny Cities, dancers Erak Mith, from Phnom Penh, and Aaron Lim, from Darwin, use the rituals, movement styles and language of their shared hip-hop culture to reveal the dramatically different worlds that surround them and uncover the choreographic links that unite them.

“Dancers Aaron Lim and Erak Mith are extraordinary. They blend contemporary dance, hip hop, Indigenous and traditional Cambodian dance in a thrilling, compelling mix full of incredible dynamic energy and fluid grace…. The audience is so close you can see and smell the sweat pouring off them and hear the squeak of their shoes… This was a fascinating, mesmerising dance dialogue/battle about two cultures colliding.” - Lynne Lancaster, Sydney Arts Guide, July 2019

Inspiring figures

by Nandini

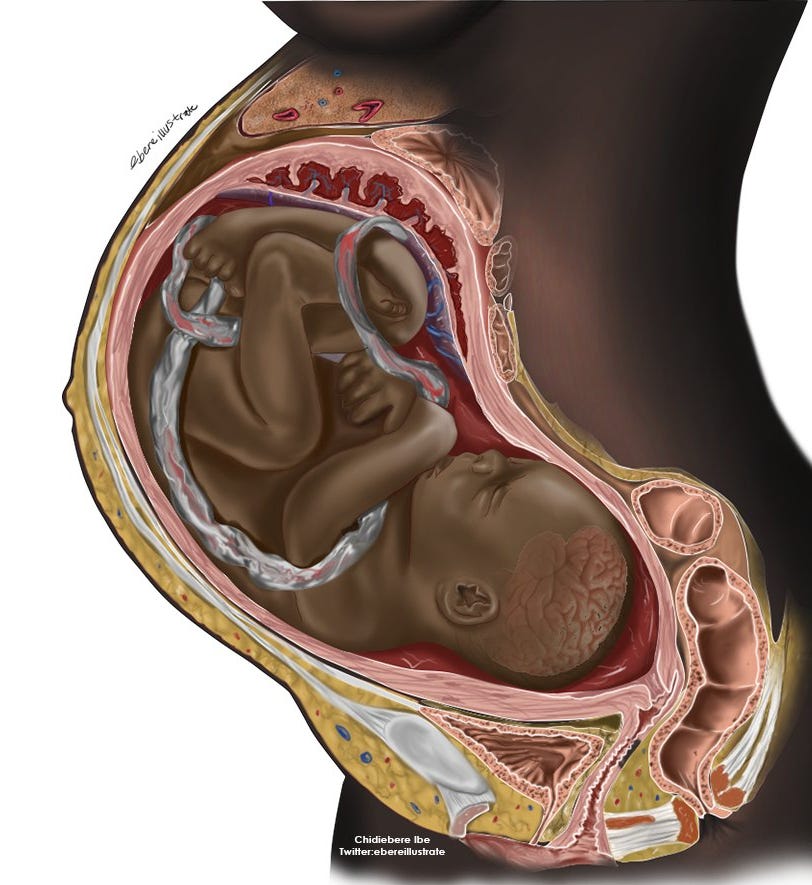

Chidiebere Ibe - @ebereillustrate

Chidiebere Ibe is a Nigerian medical illustrator and a student at Kyiv Medical University in Ukraine. In November 2021 his medical illustration of a pregnant mother and her foetus caused a social media storm. What was so special about these drawings that caused a stir? His illustration was simply that of a Black mother and foetus. However, for some people, it was the first time they’d seen an illustration of a Black foetus.

Ibe wanted to show people what certain conditions look like for Black people – and to normalise the diversity of our bodies. Since the release of Ibe’s pictures the Royal College of Midwives has said it will be increasing its efforts to diversify. In the UK Black women are five times more likely to die during childbirth than White women.

Malone Mukwende - @malone_mk

Malone Mukwende, a London-based medical student, identified a similar fundamental problem: almost all the images and data used in medical teaching was based on studies of White patients. Mukwende recently launched both a medical handbook of skin conditions on people of colour’s skin, Mind the Gap, and Hutano, a new online platform intended to empower people with knowledge about their health.

A medical student contacted Mukwende to say that all the books and reference images they used in his country of Zimbabwe were also from White skin. Zimbabwe achieved independence from British colonial rule in 1980. However, medical textbooks featuring White skin are still used more than 40 years later, in a country where less than 1% of the population are White. Mukwende, interviewed for Time magazine, said

“It makes you question and wonder how come in the continent of Africa… there isn’t an established [local] source or resource. There are so many people locally on the ground who know this stuff. But… it’s not being transitioned from individual knowledge into textbooks and resources to help to teach people”.

Chidiebere Ibe has been invited to include his illustrations in the second edition of Mind the Gap: A Clinical Handbook of Signs and Symptoms in Black and Brown Skin.

The team at Mind the Gap are constantly on the look out for images of medical conditions in non-White skin. It’s easy to submit a picture (patient consent is essential). Simply complete the consent form and email the picture of the medical condition to info@blackandbrownskin.co.uk.

Suggested reflections

What are the likely consequences of medicine being taught using images of, and data from, White patients? How might this contribute to inequalities in health outcomes between patients that are White and those that are people of colour?

How does the history of colonialism continue to impact on the lives of people of colour and White people today?